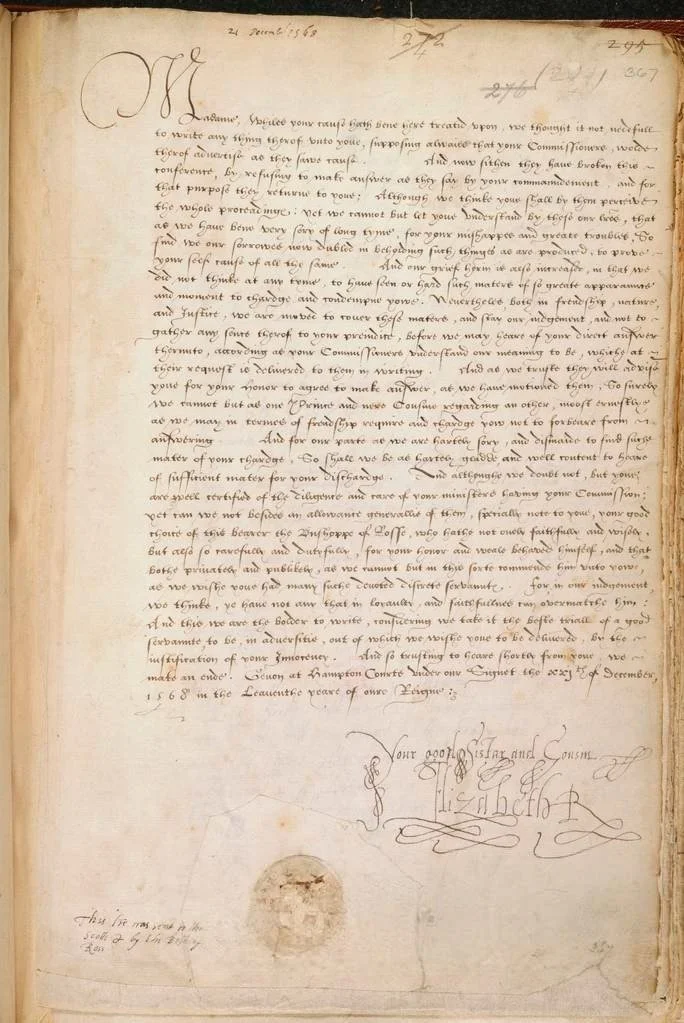

“Your good Sistar and Cousin”: Elizabeth I’s Letter to Mary, Queen of Scots (21 December 1568)

Elizabeth I’s letter to Queen Mary

A Letter in the Eye of a Political Storm

In the winter of 1568, Europe’s eyes were fixed on a drama between two queens: Elizabeth I of England and her cousin, Mary Stuart, Queen of Scots. Mary had been forced to abdicate her throne in Scotland after a series of scandals. Her controversial marriage to the Earl of Bothwell, accusations surrounding the murder of her husband Lord Darnley and rebellions from powerful nobles. Seeking refuge, she crossed into England, hoping her cousin Elizabeth would offer protection.

Instead, Elizabeth had Mary placed under house arrest. The question of Mary’s guilt or innocence and whether she could ever safely return to power became the subject of an inquiry in England. It was in this tense atmosphere that Elizabeth wrote the letter of 21 December 1568, from Hampton Court Palace.

Full Transcription

Queen Elizabeth I → Mary, Queen of Scots

(Given at Hampton Court, under our signet, the 21st of December, 1568, in the eleventh yeare of our reigne.)

“

Madame, whilst your cause hath bene here treated upon, we thought it not nedefull to write any thing thereof unto you, supposing alwaies that your commissioners would thereof advertise as they saw cause; and sithen they have broken this conference, by refusing to make answer, as they say, by your commandement, and for that purpose they returne to you, although we thinke you shall by them perceive the whole proceeding, yet we cannot but let you understand by these our letters, that as we have bene very sorry of long tyme, for your mishappes and great troubles, so find we our sorrowes now doubled in beholding such thinges as are produced to prove your selfe the cause of all the same. For wee marvell much that you that haue the singular favor of God and the kindred of the princes of these our realmes should of your selfe handle your selfe so frowardly as to breake the acquaintance and traitory of your auncient followers and friends, and to suffer yourself to be surprised with such as haue been your enemies. And so considering the great mischief that may grow thereby, both to you and to this our realme, we thought it necessary to make this open proclamation of our mind in this behalf. …

Given at Hampton Court, under our signet, the 21st of December, 1568, in the eleventh yeare of our reigne.

Your good Sistar and Cousin,

Elizabeth R.

“

The letter Queen Elizabeth the first sent to Queen Mary | Letter from Elizabeth I to Mary, Queen of Scots, 21 December 1568. Cotton MS Caligula C I, f. 367. British Library Board

(Source: Bridgeman Images)

Reading Between the Lines

Elizabeth’s words reveal the delicate dance of Tudor diplomacy. On the surface, she expresses sympathy: “we have bene very sorry… for your mishappes and great troubles.” But the sympathy is edged with accusation. Elizabeth stresses that evidence points to Mary being “the cause of all the same”; a careful way of saying that Mary’s own choices had led her to ruin.

Diplomacy as Performance. Elizabeth couches her reproach in the language of sisterly care, yet she makes her judgment clear.

Royal Kinship. By calling herself Mary’s “good Sistar and Cousin,” Elizabeth emphasizes blood ties, but also hierarchy: she is the elder, the advisor, the queen who decides Mary’s fate.

Politics Behind Politeness. Every word is calculated. Elizabeth is not merely writing to comfort Mary: she is shaping the narrative for commissioners, courtiers, and the European stage.

Historical Context

The Inquiry at York and Westminster. In 1568, English commissioners examined evidence about Mary’s role in Darnley’s murder, including the infamous “Casket Letters.” Mary refused to recognize the court’s authority, while Elizabeth avoided passing a final judgment, preferring to keep Mary in limbo.

Mary’s Captivity. This letter reflects Elizabeth’s strategy: sympathy without release. Mary would spend 19 years in captivity in England, before being executed in 1587 after being implicated in the Babington Plot against Elizabeth.

Two Queens, Two Images. Elizabeth styled herself as the cautious guardian of Protestant England, while Mary was seen by many Catholics as the rightful queen: a living threat to Elizabeth’s throne. This letter is one fragment of their long rivalry.

Manuscript Image (Where to See It)

The British Library holds the original manuscript under the shelfmark Cotton MS Caligula C I, f. 367. For visual use, reproductions are available via image licensing archives such as Bridgeman Images (also attached above)

A Lettre Reflection

Elizabeth’s letter shows us how letters were never just private exchanges: they were tools of power. In a few lines, she expresses care, delivers judgment, and establishes her authority. It is both a personal message to her cousin and a political document with international weight.

At Lettre, we see this as a perfect example of what letters capture: humanity mixed with history, affection tangled with accusation, and the quiet diplomacy that shaped nations.

Final Thoughts

Elizabeth’s 1568 letter to Mary is more than parchment and ink. It is a queen’s attempt to manage a dangerous cousin, a rival claimant to the throne, and a symbol of the anxieties that haunted Tudor England.

When Elizabeth signed off “Your good Sistar and Cousin,” it was less a gesture of intimacy than a reminder of control. For us today, this letter remains a poignant relic: a glimpse into the fragile threads of kinship and rivalry, faith and power, that bound two queens and determined the fate of a kingdom.